After the end of a long semester, a wonderful wedding, and settling back into things (enjoying the beautiful summer!), I’m finally back at it.

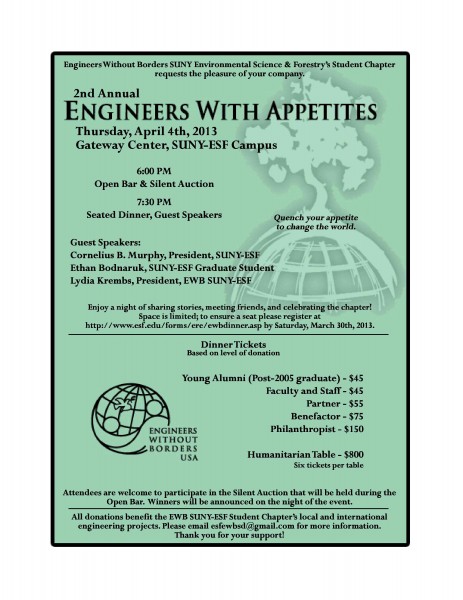

Here’s the talk I gave at an Engineers Without Borders event – a fundraiser for our projects called Engineers With Appetites. I hope you enjoy and look forward to your feedback!

[First I thanked everyone (cooks, servers, all the effort students put into the event, etc. etc. How proper of me!!) Comments I’m making for this post are in brackets]

I don’t know about you but I’m stuffed. As we digest this great food and feel our satiated bellies and appetites, I want to celebrate and talk about a different kind of appetite… a different kind of hunger… one that I hope will never be satiated in any of you.

This is the hunger and drive for the alleviation of poverty, for justice, to work for positive change and to keep a firm commitment to the self-determination and respect of everyone we work with, help, and learn from – whether here or in a developing country.

And I’m amazed and encouraged by what I’ve already seen during this year with Engineers for a Sustainable World. All these busy engineering and other students are really hungry to see change in the world.

You [students] should all be proud of yourselves, and know that you are an inspiring force for good. Even mundane topics and procedures at meetings are fun. I’m always struck by your joy and passion. That’s really needed to make a difference. We can take the problems of the world seriously while still having fun and enjoying the good things around us.

But… My only issue – my beef – with the club [dramatic pause] is the name change in progress from Engineers Without Borders to Engineers for a Sustainable World. What’s wrong with EWB? I mean, it’s a good name — a GREAT acronym. E W B. Ethan Wesley Bodnaruk. [me]

[Pause…laughter was pretty decent, by the way. I had a big grin as usual]

Through this club you’re already being exposed early in your engineering careers to the overlap of engineering, science, and technology with social issues, poverty, equality, sustainability, economics, and the other complex realities of life that shape so much of the world around us. This is becoming the norm for Ecological engineering, but it’s more rare in many other fields of engineering and science.

I think in general scientists and engineers don’t engage as much as they could in moral and ethical issues related to their work, as well as the broader ethical or moral issues we face as a society.

Engineers need to be highly aware and versed in ethics, human behavior, ulterior motives, and so forth. Scientists and Engineers have a major role in the development and use of technology, and technology has an ever-increasing power to do both harm and good. And we need to keep in mind that it’s easier to destroy than create or restore, which I’ll talk more about later.

What are some possible reasons engineers and scientists don’t engage in these issues and subjects? You can let me know if I’ve left any big ones out, but here are some ideas.

- People are complicated: sometimes rational, sometimes pretty irrational

- We’re used to equations and concrete, quantitative results to problems with solutions. The human aspect is so much less predictable. But it’s also exciting to use a different part of your brain. Engaging with the people side of things can lead to new experiences as you know from your travels. And in a way, people are puzzles to solve too – not just the equations. Oftentimes technology is the smaller puzzle to solve, and how to make it truly relevant and helpful, to integrate it into a society or practice is the hard part. [Thinking of technology solutions to improve life in developing countries, etc.]

- In school, we’re used to working on our own or just with other engineers – No consulting with anyone else. Communication and understanding other viewpoints and ways people think is key to getting stuff done in the real world.

- Another potential reason we don’t engage as much is that well, sometimes [big smile], sometimes we engineers can be a bit socially awkward! I know I feel it sometimes!!

- Another reason is that in our society critical thought and analysis can easily become compartmentalized and it can be taboo or controversial to engage topics that are not purely technical.

Earlier I mentioned the club’s name change. In deciding their new name, one top contender was “Humanitarians for a Sustainable World”. The choice of the word humanitarian emphasized the group’s desire to reach out even more to non-engineers. This is a great impulse, but I’m glad we kept Engineers in the title because it’s important and unique to emphasize engineers engaging in society. It’s amazing that this group of engineers sees themselves as humanitarians and wants to reach out to non-engineers. But technical know-how is so often used for destruction or just to advance business as usual, so it’s amazing and important to highlight its positive uses, like through this club and even its name.

I want to touch a little more on the role of science and engineering in destruction. One major way this happens is through weapons technology and defense. I realize this is really controversial, but it’s important that scientists and engineers be able to talk about things like this. There’s pros and cons, plenty of philosophy, and plenty of debate to be had about defensive and offensive weapon technology and use. But I just want to give a quick idea of where I’m coming from.

- For my undergrad, I went to a small science and engineering college called Harvey Mudd. About half of the engineering majors went on to work for defense contractors. It’s a huge employment opportunity.

- We had to do a senior design project, and reading the descriptions I found one about cryostats. What could be cooler than cooling stuff down to super low temperatures? I signed up for it, and when the project started I learned that it was for a missile targeting system. The sensor in an infrared heat seeking missile has to be cooled down to very low temperatures to work optimally. I didn’t want to put my symbolic blood, sweat, and tears into something that really would be used to create real blood, sweat and tears. I switched projects and it was somewhat complicated to make that happen, but I was glad I did.

- After hanging out in some monasteries for a year, I got a Master’s in Nuclear Engineering at North Carolina State. Back then I wanted to work in nonproliferation and was interested in the international aspects and issues of science, engineering, and weapons. So you might imagine I have some interest in the history of the development of the atomic bomb.

Many people have strong feelings about nuclear weapons, and more commonly discussed moral issues surrounding them are the wisdom of having enough weapons to essentially wipe out all life on the surface of the earth, why certain countries are still allowed to have them but others are prohibited, and should the US have used them on Japan in WWII. Some argue their use ended the war, but then again they disproportionally targeted civilians. Also, some people say Japan only surrendered because of the bombs, but then others say that Japan’s determination to fight to the end was fueled by their own government’s propaganda – that the gov’t was lying to its people, saying the war was going well when really they couldn’t hold out and were close to surrendering irrespective of the bombs.

Another angle is that of the scientists and engineers who worked on the bomb in the Manhattan Project. As much as possible, their work and interactions were compartmentalized to minimize the number of people who would fully realize the scope and magnitude of what they were working on. The scientific leaders who were in the know, like Robert Oppenheimer, thought they would have some say on whether or how the weapons were used. They were wrong, and after Hiroshima and Nagasaki many of them immediately became among the most outspoken opponents of nuclear weapons.

Germany was trying to develop nuclear weapons during WWII and this fueled the American effort. There are strong indications, though, that the scientists and engineers in the American program were intentionally misled later in the effort that Germany was not starting to lose and they were not told that Germany’s nuclear efforts were crippled by targeted attacks.

One of my favorite authors, the American physicist Freeman Dyson, knew many of those involved in making the bomb. He’s written on the subject and offered fascinating insights. It was a very small but close-knit, international group of scientists who discovered and were working on fission before the Manhattan Project. They were extremely excited about something so new and its potential for cheap energy. They also realized the potential for a weapon of incredible strength. What’s fascinating to me is that initial reactions by political leaders to the idea of a fission bomb was extremely negative or dismissive. Fission was a totally new idea, and it would take so much money and time to get a weapon out of it. It was a pipe dream to leaders who are usually fairly practical-minded.

Later, as attitudes began to change, Dyson pointed out that the scientists had the opportunity to set rules and ethics within their group, to decide if they would pursue the bomb or not. They missed that chance and within a couple of years all talk of fission was highly classified, the scientists weren’t able to meet at international conferences anymore, and the fires of nationalism were strong and pushing the scientists each to serve their own countries.

I for one find this tremendously interesting especially as it brings in politics, ethical issues, deception, nationalism, and so forth.

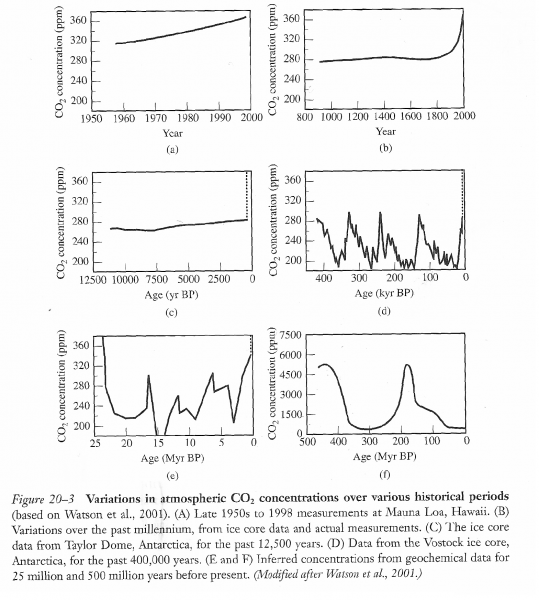

In general, the role of science in ethics, morality, and decision making is a hot topic right now. Climate change has of course lit fires under science, how it is communicated, and forces that resist scientifically informed decision making for their own benefit. There are some best-selling authors who have written on science and ethics or morality, like New Atheist Sam Harris and his book The Moral Landscape: How Science Can Determine Human Values.

ASU hosted a discussion on whether science can tell us right from wrong with a bioethicist, Sam Harris (neuroscience and philosophy background), philosophers, and a physicist.

Michael Schermer is a well-known “skeptic” with a column in Sci American. He wrote a similarly titled article recently, saying yes it can.

And Harris described a moral landscape as 3D topography plot of happiness or well-being. There are many peaks and many valleys corresponding to We can at least identify those peaks and those troughs. I really like this image and this way of thinking.

So … Can Science Tell us Right from Wrong? I don’t think so exactly, but it can come really close. And that’s valuable.

We could call it quantitative empathy or quantitative compassion. In our complex world there’s a growing need to quantifying the results of our actions and programs. Science – even just at the level of statistics – can tell us if we’re meeting goals and can tell us a lot about how actions affect people. We can also investigate the likely effects of certain cultural practices or stereotypes. In what ways does a practice contribute to how people flourish or don’t. Who does a practice, idea, or policy favor or not favor? What do the people who have control over a given action or policy think and what do the people who are affected by it think? (Role of women in some societies fetching water).

There was a recent talk here at school on gender roles and water. The speaker showed pictures of how community planning around water began to occur after some focus on the topic, but no women were involved! Yet they are the ones most affected by it, spending hours each day fetching water. In general it’s not a good idea to leave out half of your resources from planning, especially when there’s such a difference between the experiences of those halves. Certainly there will be key insights from the women – the group left out. Even more, a friend told a story about a water project near her hometown in Afghanistan that failed after a large storm. Men in the community scrapped it, selling the resources (metal piping, etc.) instead of looking into fixing it, perhaps thinking that the women would just go back to the way things were and that that wasn’t so bad for them as men.

Further statistics from the World Bank, as cited in the sequel to the popular book “Three Cups of Tea” about building schools and education for girls in the Middle East, show that when girls and women are educated they are much more likely to teach literacy skills to other family members, all sorts of health and development indicators go up, and women often start their own businesses that produce income and meet important needs.

So even just at the level of statistics (not even going into psychology, social well-being, power dynamics, etc.) there are plenty of reasons, for instance, to question limited roles for women. So I would say it’s fair to say that science comes out against that. Although of course no equation says that directly – that’s just silly to only equate science with fundamental equations.

Let’s move on to another example important to me: Haiti and issues of foreign aid.

- 97% of our government’s international aid (from the United States Agency for International Development, USAID) comes back to the US (American contractors, NGO’s etc.)

- <1% of earthquake aid to Haiti stayed local. This is a ratio of about 33:1 on the ultimate local vs. international destination or fate of aid. Would keeping that aid in Haiti have a better effect by a factor of 33? More? Who’s back is getting scratched the way things currently are?

USAID: goal of 30% aid to stay local by 2015 or 2020, I forget which. Much improved goal. But large aid agencies that are recipients of USAID money are vigorously opposing it. They formed their own lobby for Congress and are spending millions lobbying against it. No joke.

You sometimes seem like a jerk when you criticize aid, but it’s important that our programs are effective and that aid is effective. But at least USAID is pretty transparent that their mission is first of all to advance US interests abroad. We just hope these interests are more to help people than to secure power or influence. If so, the money would be way more effective if it stayed local.

On to my last topic. I want to point out that just because I’m talking about the role of science, statistics, quantitative measures about issues related to moral issues doesn’t mean I’m saying we shouldn’t also use feelings, stories, and myths. I was talking with a friend lately about Star Trek the Next Generation – I grew up watching that. The android’s name is Data, but I had forgotten that his “twin” and evil brother was Lore. Basically, myth. If not set up as opposites, that’s at least a clever contrast.

One example with a sciency angle that I think of when it comes to the usefulness of myth or lore is the idea that Einstein struggled with math when he was young and failed at least one of his math courses (maybe it was just because he was bored?)

Regardless, this story actually isn’t true although it’s very widely told and repeated. It shows that even uber geniuses have their struggles and obstacles to overcome. I remember reading a quote by Einstein that addressed this rumor (apparently prevalent even during his life), where he said by the time he was an early teen he had mastered differential equations and linear algebra! So much for that one!

Even though it’s not a true story, I still really like it and can get inspiration from it. There’s nothing wrong with that. If ever a discussion about its factual truth comes up, though, we should be honest about it! There may be some parallels to draw here with religion, but that’s for another time.

Conclusion

This was a small tour de force of a host of different topics related to engineers and scientists engaging in moral and ethical issues and projects related to human well-being. The author I mentioned earlier surrounding the atomic bomb wrote a book called Scientist as Rebel. I like the idea of Scientist as Rebel, searching for depth and clarity in the world around us and in human interactions. Being a rebel is good, as long as we remain a rebels with a cause — A meaningful cause that affects peoples’ lives.

But if “Scientist as Rebel” doesn’t really jive with you, I can understand that! I’ll be very happy if we can agree to be engineers with tremendous appetites that never diminish.

[Puts up the big burger picture]. What would the world be like if we all had appetites – of the kind we’ve been talking about here tonight – as big as this guy’s?

Thank you.