Note: I wrote this in early fall and tried to submit it to the Huffington Post, but to no avail.

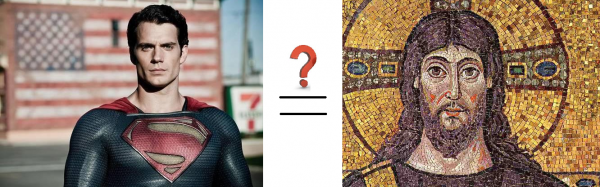

This summer’s movie, The Man of Steel, deeply and beautifully focused on Clark Kent’s (Superman’s) struggles and moral development. Christian pastors were invited to free advance screenings and were provided with sermon notes titled “Jesus as the First Superhero”. Was Jesus like an American superhero? Did he endorse violence as a way to fight evil and bring about righteousness?

The Man of Steel and Jesus, the Man of Love, are not the same. Instead of Superman, Jonathan Kent (Clark or Superman’s father) was actually the Jesus figure, and Superman’s task was to deeply learn and embody his father’s spirit.

Accordingly, the Christian Church is like Superman not because it’s the hero that saved the day but because its most fundamental task is to deeply learn, imbibe, and embody Jesus’ spirit. The Superman of this movie did a much better job of it than the Christian Church as a whole.

Clark was different, so he was bullied as a young child. His x-ray vision and super hearing led to panic attacks and he’d run out of class desperately searching for peace from his overwhelming senses. He seemed weak, especially because Jonathan taught him never to fight back. As Clark got older, Jonathan emphasized that how he responded to the hatred, fear, and arrogance of others was his choice and would determine what kind of a man he would grow up to be.

Jonathan was real with Clark about the difficulties of nonviolence. He wanted the bullies to get what was coming to them but knew this was a dangerous path for anyone and especially for Clark. When those with overwhelming power retaliate, it only creates more fear, mistrust, and alienation. Clark would never gain the trust and admiration of humanity this way.

Jesus’ disciples also struggled with issues of violence, retributive justice, and power. They (and their culture) expected the Messiah to be a king who would inflict vengeance upon Israel’s enemies. They wanted Jesus to zap people who failed to show them hospitality and to defend Jesus with the sword. Peter couldn’t bear to have his feet washed by Jesus because he so strongly thought only servants should wash their master’s feet and not vice versa. Jesus rebuked the disciples each time.

Jesus represented a different relationship to power, violence, and status; he likened his way to a narrow gate that few enter but leads to life. The gate that leads to destruction (violence, control, and power over others) is a wide gate that many enter (Matt. 7:13-14).

In the movie, Jonathan risked his life to help others during a tornado. He knew it was dangerous but felt the risk of Clark revealing his powers was too great. Jonathan saved the people but died in the process, teaching Clark what love looks like and that true strength comes from within.

Jesus also seemed to think that his best hope of getting through to the disciples – of showing them once and for all who he was and what he stood for – was to accept his death at the hands of the religious and political authorities. His death would shock them out of their old ways of thinking, making room for a new Spirit to thrive within them. For a few centuries Christianity held on to the spirit of Jesus, represented a radically different way of life based on love, and refused to take part in violence.

Although there’s been a push to equate Jesus and Superman, the movie provides a much stronger case for Jonathan as Jesus, with Superman being similar to Christianity because they share the fundamental task of becoming like Jonathan or Jesus.

Nonviolence and kicking some alien butt

Kryptonians – people from Clark’s planet – arrived at Earth and wanted vengeance on Clark for the past actions of his parents. They broke their promise to spare humanity if Clark turned himself over. Clark, now Superman, fought back and killed the Kryptonian leader with his own hands.

To create the violent plot and justify the massive destruction caused by Superman (his fighting leveled several towns), the Kryptonians had to be portrayed as purely evil, possessing no conscience, and having technology that could quickly and easily wipe out the human race. It reminds me of how war is often framed and justified in public debate…

Superman was nonviolent toward humanity and turned to violence only as a last resort against genocidal invading aliens: a far-fetched occurrence. What would the world be like if Christianity was committed to justice and righteousness based on nonviolence?

Superman’s real strength was reflected in his refusal to retaliate against the arrogance and evil inside humanity. He had imbibed his father’s vision to be a beacon of hope and light. Without this, he could never win the hearts and minds of the whole human race.

Nonviolence and its foundation, radical love, at first make us weak but invite us into the knowledge and experience of a power that gives us strength, passion, purpose, and hope even in the midst of suffering.

Moral training and spiritual practices fuel and nourish us. Deep reflection and contemplation of the life, teaching, and spirit of Jesus is one such practice. Gandhi studied the New Testament daily and was further transformed by Jesus’ love, spirituality, and power despite (or because of?) his rejection of dogmatic Christianity.

Jesus told a parable of two sons that should challenge the traditional dogma of salvation for Christians alone. A father told his two sons to work in his vineyard. The first said yes, but didn’t do it. The second said no, but changed his mind and worked. Jesus used this parable to point out that the religious leaders – those who said the right things and acted righteous – were actually far less righteous than the tax collectors and prostitutes they considered outcasts (Matt. 21:28-32). Gandhi was like the second son because he rejected Christian doctrine but imbibed and lived out the radical love of Jesus.

Jesus also told a parable in which he is the vine and the disciples are the branches drawing life and energy from him. He warns them that if they aren’t truly attached to the vine they “cannot bear fruit” and “cannot do anything” (John 15) – essentially that they would make a mess of the world, as Christianity has often done.

We can still embrace the worldview of a cosmic battle of good versus evil so prevalent in human cultures and religions, but we have to fight in a way that’s pure and increases the goodness in the world. Nonviolence is good, life-giving, and with discipline and creativity it’s practical. In this way, we can all see Jesus as a savior of the world.